It was year two of that thing with \"Two-Six,\" the 26-year-old waterfront director at summer camp, and still, no one knew the secret—that is, no one except my best-best friend, Annie, who grew up right down the street from me. I was just thirteen in year one when it started, but Annie, who was a whole year younger than I was, thought it was pretty cool that I had this 26-year-old “boyfriend” from camp who she could never, ever tell anyone about—no matter what. As Two-Six had explained to me, and as I had explained to Annie, nobody else could possibly understand just how \"mature and unlike other thirteen-year-olds\" I was. And if anyone ever found out, they'd be so jealous that they'd get him in a whole lot of trouble.

So, one evening back at camp during year two of that thing, I sat with my cabin group after dinner in the dining hall which was alive with kids playing Patty-cake, singing the “Noah's Arky-Arky” song, and trying to slurp the last bit of bug juice out of tall plastic cups. We were seven 14-year-olds, serendipitously gathered from doctors' homes, inner-cities, children's homes, and from the set of a CBS television drama series. Perched on wooden benches with peeling navy-blue paint, we giggled and talked about cute boys, then stretched our necks to see which of those cute boys on the other side of the dining hall might notice us.

Including our counselor, we were evenly distributed by twos on each side of a heavy, square wooden table that matched our pseudo-navy-blue benches—until my counselor got up and left me alone on my side of the table.

My heart stopped for a split-second déjà vu moment from one year earlier, at age thirteen, when I had just met \"Two-Six.\" I was likewise seated with my cabin group, but when our counselor casually walked away from the dinner table that night, \"Two-Six\" slipped into her spot on the bench right next to me.

As head lifeguard and overseer of all the fun waterfront events at camp, “Two-Six” was extremely popular with all the kids. He had a way of contorting his face and bulging his eyes when he talked or told a joke that made you laugh so hard that his marked unattractiveness and the discoloration of his teeth went unnoticed. That night at the dinner table he was in full throttle telling one joke after another with such animation that he distracted the other girls with humor while he slid his hand up and down my thigh, stopping when he reached the elastic in the leg of my underwear, partially exposed by then under my loose cotton shorts.

I sat still, completely frozen by the outrageous liberty he took with me, yet entirely determined to live up to how \"mature and unlike other thirteen-year-olds\" I was.

What is he doing? Is he in love with me? Are the counselors and other staff going to be mad at me or jealous of me? How would an older girl act right now?

Every chance he got, Two-Six told me how beautiful and intelligent I was, how mature I was, and again, how other people would simply not understand the dynamic of him liking me because they were just too immature or too jealous.

And I believed him. After all, I was an honor roll student two grades ahead of kids my age at school. No one ever had to ask me if I had gotten my homework done, and every month I would walk across town and pay bills for my family. So, having a 26-year-old boyfriend made perfectly good sense, right?

“Two-Six” started making plans to meet me in the dark somewhere just off the path between the back door of my cabin and the girls' latrine after my showers at night. He would run his tongue all over my neck and in my mouth, and he would run his hands across my buttocks and up my thighs. But now he no longer stopped when he reached the elastic of my underwear. He would use his finger to penetrate me where only a junior tampon had scarcely been. I said nothing. I did not understand how this was a good thing, and I was always afraid of getting caught.

After six weeks of camp during year one, I returned home feeling physically spent. When the doctor diagnosed me with mononucleosis, he laughed as if he had never heard of something so foolish.

\"Did you know that mononucleosis is called the kissing disease?\" he asked.

I still don't know what was so funny about that.

I had read about mono in a teen magazine on display at the camp infirmary, but I didn't dare tell the doctor I knew where it came from because I figured he'd laugh at that, too.

But now I had my chance. Mononucleosis was the subject on the table, so I could tell my mom what was going on with \"Two-Six.\"

“So, somebody been kissin' all over you?” she asked as we walked away from the doctor's office.

“Yes,” I said with the weight of the world falling from my 13-year-old shoulders.

Thank God, I thought. Now, this can all come out in the open.

My mother said nothing.

Instead, she turned her head and walked away from me as if in disgust.

I felt filthy. Misunderstood, but filthy, just the same.

The two of us never talked about that moment again.

Eventually, letters started arriving from \"Two-Six,\" saying how much he missed me and asking if I would be returning to camp the next summer. I was a ball of mixed emotions—a girl who had loved camp since age eight and who wanted to join her every-year-at-camp friends in a summer-long slumber party while simultaneously feeling the dread of having to be that girl who was so \"mature and unlike other thirteen . . . ,\" now fourteen-year-olds.

“Yes,” I told him. I would be returning to camp. And once I arrived, I was shocked at how quickly that thing was once again underway. On the very first day of year two, I took a shortcut through the dark, empty dining hall to drop off papers at the infirmary without walking through the woods. To my great surprise, \"Two-Six\" was walking through from the other end, and his tongue was in my mouth and his finger in my bottom before I could say, \"Jack Rabbit.\"

The evening meetings on my way back from the girls' latrine to my cabin continued as though there had been no break in time or space between year one and year two . . . until that evening at dinner when my counselor left my side to talk to another female counselor and their supervisor. From my position at the dinner table, I heard far more than I ever wanted to hear or know.

“Two-Six” had been doing that thing with another girl at camp who was even younger than I was. She told her counselor who told all the other female counselors and their boss. I heard them say they couldn't believe what the little girl said, so they asked Two-Six's girlfriend to question him. His response was, “I would never mess around with nothin' that young.”

“Oh, yes, he would,” I whispered to myself in a brief moment of truth. “Cause he did it to me.”

After that, I heard nothing else but my own thoughts.

That poor girl. This is all my fault, isn't it? What if I had just said something? Somebody, help me. I don't know what to do. Are they already on to me? Do they already know? If I look up from my dinner plate, will they all be looking back at me?

Get up, right now. This is your chance. Go and tell those counselors about that thing with “Two-Six.” Tell them what happened right here at the dining hall. Tell them to camp out near the path between the girls' cabins and the latrine. Tell them something.

Silence.

And what girlfriend were they talking about anyway?

My crotch burned as if I had urinated in my shorts, my stomach ached, but my heart ached more.

We were near the end of my camping season, thank God. I returned home to find Lou Rawls' new song, \"You'll Never Find Another Love Like Mine,\" blasting from someone's car radio every seven minutes, and I thought I would die every single time.

What is wrong with me? Why do I feel so scared all the time? Will anyone else ever like me? Am I just too mature?

I was literally sick—frequently stealing away to cry it out or just to sit and stare in the dark. Whatever it was that bothered me most, I could not articulate. I just felt an all-around misery and sadness that I sometimes could not hide very well. A few months later, just after my fifteenth birthday, my mother took me to see a psychologist who thought my responses to his rather mundane questions were unremarkable. Finally, he ended the discussion by directing this comment to my mother: \"Well, mom, I guess it's just tough to be fifteen.\"

And that was that.

I went back to camp that next summer determined to enjoy it for what I always loved about camp: friends, campfires, songs, and skits—the things that made it a lovely place to be.

\"Two-Six\" was not there, but people were talking about him. I made no mention of his name. Still, no one knew the secret, and no one knew that his letters continued to arrive at my house. Mostly, he talked about how the \"girlfriend\" I had heard about was a girl he only pretended to go out with to hide what was going on with me, how glad he was I hadn't said anything to the powers that be, and how that made me even more \"mature and unlike other girls my age.\"

I was fifteen, in my senior year of high school where I did not belong, scared to death of entering the world of college where I did not belong, and unable to blow the whistle on a man with whom I did not belong. I hadn't seen \"Two-Six\" in more than a year. But one month, I received a letter from him inviting me to visit him while he traveled from the Midwest to visit \"friends from camp\" who lived near me. The friends he would be visiting lived about one hour from me by train.

I didn't know exactly how to feel, but by some strange stroke of providence, at that very time, I had reached a point in my reading through my “novel of the week” pick, where a female character has a confrontational coming of age moment when she visits a friend on the same-named street as these friends of \"Two-Six.\" I thought that in some constellation of stars, that meant I, too, would have life settled by the end of this visit.

So, in that weird way that life imitates art, I prepared to meet him when that day came. I still didn't know quite how to feel or what to think. I just knew I had to get there to at least grant myself some peace.

I chose what I wore carefully, although I didn't know what message I should convey or why. I wore a blue denim A-line jumper with a buckle across the chest area over a blue plaid blouse and flat red shoes.

No one on earth knew where I was going on that day except “Two-Six.” I was so “mature and unlike other girls my age” that no one ever had to ask my whereabouts. I was always exactly where I should have been.

When I arrived at the friends-from-camp-house, everyone there—all strangers to me, was at least ten years older than I was and busied themselves by playing cards and drinking. One of them said hello and motioned to “Two-Six” that I was there. He took me to a back room where I shouldn't have gone, said he couldn't believe I was there, stuck his tongue in my mouth, and felt around my A-line jumper. There was no talk. There was no “novel of the week moment.” I was thoroughly disgusted, confused, and out of there in a handful of minutes.

I knew that was the last time I would ever see \"Two-Six,\" and I was relieved. I thought ahead to the one thing that didn't frighten me about entering a new chapter of life, and that was the opportunity to start all over. When I got home, I bundled together all those letters from \"Two-Six,\" walked down the street and dumped them into a public trash can. I had to get him out of the way physically, and that was the most natural thing I could think of to do.

I had no concept at that time of how much I needed to work through everything that had happened in those two years; and indeed, I swept it under the proverbial rug for a long time simply as that thing with “Two-Six” as though everyone had something just like it tucked away in their life. But I couldn't sweep it away for long, because there were other “that things” which eventually left no more room under the rug.

I came to Christ as a college student, but had no idea how to approach the abuse that had already happened several times in my life and sort of hoped it would eventually fall off my radar. But by the time I was 27, I had experienced sexual abuse from at least six different males, and I felt more than just picked on a little bit.

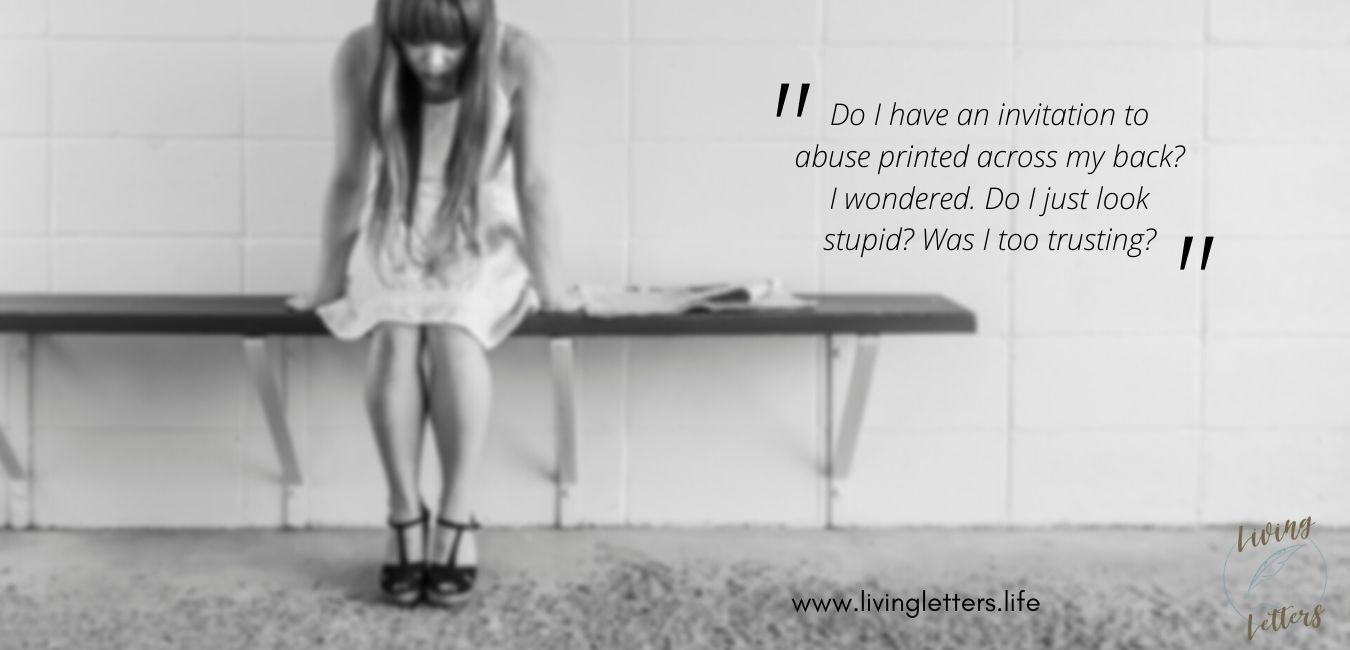

Do I have an invitation to abuse printed across my back? I wondered. Do I just look stupid? Was I too trusting?

Once I was married and had a baby, the issue of abuse lived at the forefront of my mind. During a three-and-a-half-year stint with a Christian counselor, a friend who had an experience like mine suggested we expose “Two-Six” in case he still worked with kids in camps. I saw this as a way to redeem my silence when I should have spoken up for that little girl in year two of that thing.

I was ready. I was no longer a scared little girl, but a grown woman, wife, and mother with a mission. Nothing would deter me now. The moment I googled his full name, an enormous image of \"Two-Six\" popped up in the same likeness as his image might have been when I met him thirty-four years earlier. Then I noticed the picture was attached to his obituary.

If there were ever a way to know for sure if you have sufficiently dealt with an issue like this, it would be wrapped up in this scenario. Knowing for sure this man would never ever do that thing to anyone else and that God Almighty would deal with him accordingly should have been enough for me, but it was not.

I didn't want to find this man dead; I wanted to pull the trigger. I wanted to be the one to render him unable to perpetuate his egregious acts on children. At that moment, I didn't like living with what God had chosen to do.

Even my prayers for quite a while after that were the damning, imprecatory prayers of a wounded woman unwilling to be healed. I had no vision whatsoever for the good or redemptive purpose behind all that had happened, and could not have even been engaged in a discussion about it.

Then God intervened with the precious gift of His Word. One day He specifically led me to read the Genesis 34 account of the tragedy in the life of Dinah, daughter of Jacob. When Jacob and his family move to Shechem, Dinah goes out to visit the women. While she is out, the son of the ruler of Shechem sees Dinah, takes her, and rapes her.

Jacob, Dinah's father, does not immediately tell his family what has happened, but two of her brothers overhear the story and are livid. The brothers devise a tricky scheme that enables them to kill every male in Shechem in retaliation for their sister's rape. Jacob, however, is upset with his sons because, as he says to them, \"You have brought trouble on me by making me a stench to the Canaanites and Perizzites, the people living in this land. We are few in number, and if they join forces against me and attack me, I and my household will be destroyed\" (Genesis 34:30).

What a lackluster, selfish, can't-be-bothered response from a father to his sons concerning their response to the rape of his only daughter. It nagged at me for a long, long time—not only that Jacob, Dinah's father, doesn't care what happens to her in light of how it will affect him, but also that Dinah and her story seem to just disappear after this Genesis 34 account. Because of Jacob's flippant attitude, even the brutal retaliation of Simeon and Levi seemed insufficient to me. I wanted more.

Surely, God must care more about the rape of a woman than is indicated in this story, I thought.

Then the Lord directed me to pay more attention to what Dinah's brothers say to their father, Jacob, after his careless response to their revenge: “Should he have treated our sister like a prostitute?” (Genesis 34:31).

I read, read, and read again through the passage. Still, it wasn't until I sat down one day and listened to the reading of huge chunks from Genesis, Exodus, and Leviticus all at once that I realized God used that word, prostitute over and over again to describe how Israel, His chosen people, treated Him, their redemptive God. And He most certainly did not appreciate it. “They must no longer offer any of their sacrifices to the goat idols to whom they prostitute themselves. This is to be a lasting ordinance for them and for the generations to come” (Leviticus 17:7).

It was as if the light came on all at once. Yes, there is a horrific tragedy in the narrative that unfolds in Genesis 34 with the rape of Dinah. And yes, we are to feel her pain and feel the rage that must have built up in the hearts of her brothers, Simeon and Levi, for them to retaliate as they did. And yes, it is true that few other tragedies, if any, would ever provoke the level of fury incited by the violation of one's sister or daughter.

But we, the blood-washed reconciled ones, raptured into relationship with Almighty God through the redemptive work of Christ, are to take that pain and rage and fury and consider them as the same daggers we thrust through the heart of God when we reject Him and instead keep company with what has no lasting meaning or value. When God wants us to hear and understand Him on a level to which we have not risen, He will often use the stuff of heartache and disaster that we cannot handle or escape from without simultaneously clinging to Him.

And so, the reason we don't hear more about the rape of Dinah is that Genesis 34 is not about the rape. It is about so much more—just as my life is not about the abuse. It is likewise about so much more.

And in that, I have peace.

Send Me A Message